- B-R & H Finance - The 4 Seasons

- Posts

- B-R & H Finance ● The 4 Seasons

B-R & H Finance ● The 4 Seasons

Blabla

Table of Contents

B-R & H Finance - Purely indicative - 17.02.2026 / 18h30 CET

B-R & H Finance - Purely indicative - 17.02.2026 / 18h30 CET

Market Review

“AIDS - AI disruption syndrom”

This headline is making the rounds in markets at the moment, it’s not ours…

Since the start of February, equity markets have slowed but not collapsed. The big US indices (S&P500, Nasdaq) are down, yet the equal‑weight S&P500 has just hit a new all‑time high: it’s no longer the tech giants leading the dance, but the rest of the market. Institutional investors are being pushed to put idle cash to work, so they are rotating into more traditional sectors. In this mood of doubt, gold has climbed back above its symbolic Usd 5'000/oz threshold (Usd 4'866 last), while bitcoin is struggling around Usd 66'900.

The second key message of early February is fatigue with the AI story. On one side, investors fear the disruption AI could bring; on the other, they are starting to question the payoff on the hundreds of billions already spent. UBS has just cut its view on tech from “attractive” to “neutral”, pointing out that the hyperscalers are now pouring almost all of their operating cash flow into AI capex – a pace that is hard to sustain. The result: over Usd 1'000 billion in market cap wiped off the big AI‑linked names, even if the infrastructure suppliers (semiconductors, memory, equipment) have held up better than software, which is more exposed to fears of being replaced.

In Switzerland, the picture is simpler. Roche and Novartis are trading close to all‑time highs – Roche around Chf 500, Novartis at Chf 166.18 – confirming their status as pillars of the Swiss market. Europe and Switzerland are clear beneficiaries of the global rotation: industrials and dividend names are attracting flows at the very moment when big US tech is catching its breath. In the background, long‑term yields are drifting lower (US 10‑year around 4.05%), the dollar is easing and oil is correcting slightly.

For a long‑term investor, this start to the month doesn’t change the underlying story, but it does offer a few useful landmarks. The real question is no longer “should I be in or out of the market?”, but “where should I be invested?”, between very expensive AI plays and more reasonably valued segments. Macro signals (inflation moving back toward normal, expectations of rate cuts) support a gradual move out of cash and into risk assets, but without rushing. Our view remains to keep a diversified exposure across growth, value and real assets, while accepting that the AI theme will go through phases of doubt after a near‑straight‑line boom.

Few numbers

1.27 working days per week are now spent at home on average worldwide at the end of 2024 / start of 2025 – roughly 25% of paid days.

Employees working for a CEO under 30 spend on average 1.4 days a week working from home, versus 1.1 days when the CEO is 60 or older.

In Europe, the hybrid model accounts for 44% of jobs that can be done remotely, while fully remote roles have stabilised around 14%.

Editorial

The Kingmaker

We tend to picture him in a New York trading room, screens on before dawn, but the story starts elsewhere: in Pittsburgh, in the late 1970s, in a provincial bank where a young graduate accepts a junior management job, with no glittering pedigree and no old‑boys’ network. His name is Stanley Druckenmiller. He pores over balance sheets, dissects companies, climbs the ranks to head of equity research within a year, then strikes out on his own in 1981 by founding Duquesne Capital, a small macro fund before “macro” was fashionable, far from the glare of Wall Street. Legend has it he worked late into the night and listened closely to the world, alert to cycles, rates and currencies; always hunting for imbalances rather than stories.

That ability to sense a system on the brink is what draws the attention of another major figure of late‑20th‑century finance: George Soros. In 1988, Soros asks him to take the reins of the Quantum Fund; Druckenmiller accepts and, at 35, finds himself running one of the most feared vehicles among central banks. Their styles are complementary: Soros pushes, questions, dramatizes; Druckenmiller calculates, refines, executes. Together, they write one of the most famous chapters in FX history: the attack on sterling in September 1992. Their wager is that the UK cannot defend its currency indefinitely within the European exchange‑rate mechanism, that reserves are finite, and that a brutal rate hike would be politically untenable. The rest is history: Black Wednesday, the Bank of England capitulates, sterling tumbles, and the Soros–Druckenmiller duo is said to have made around Usd 1 billion in a single day.

In that scene, Soros will forever be the public face, accused of “breaking” the Bank of England; behind the curtain, many insiders acknowledge that it was Druckenmiller who built and carried the position, adjusting size, maturities and timing. That is where his reputation is forged. A macro‑trader able to hit a currency, a yield curve, an index, with cold force and almost literary precision: a clean sentence, without adjectives, that echoes for years. Far from the romantic image of the lone speculator, it is a systems job: reading fiscal policy, central‑bank psychology, and the exhaustion of public opinion in the face of rising rates.

After 2000, Druckenmiller’s life enters its second act: he leaves Soros, returns to Duquesne, then shuts the fund in 2010, not for lack of performance, but because he judges the pressure incompatible with his own standards. He turns his vehicle into a family office (his fortune is estimated at around Usd 11bn at end‑2025), and continues to invest his own money, and that of a few close partners, away from the tyranny of monthly reporting. Around him, a small galaxy gradually takes shape, through which future heavyweights pass: Scott Bessent, who learned the craft under Druckenmiller and Soros before becoming CIO at Soros Fund Management and then launching his own fund, Key Square, firmly in the macro tradition; Kevin Warsh, a young Morgan Stanley banker whom Druckenmiller helps bring into the Fed’s orbit and who becomes one of its youngest governors before being nominated by Donald Trump to succeed Jerome Powell. In these intersecting paths, Druckenmiller looks less like a mere money manager and more like a discreet kingmaker: spotting talent early, putting people in the right place, then letting an endless conversation unfold between markets, monetary policy and the back corridors of Washington.

Even today, well into his seventies, Druckenmiller is listened to like a veteran general who has fought several currency wars. The positions disclosed via his family office are still highly concentrated: big bets on US technology – Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta – and a strong interest in companies exposed to energy transition and metals, such as Teck Resources or Vistra. He has recently exited or sharply reduced some of the AI darlings, including Nvidia and Palantir, presumably judging that the gap between promise and price had become too wide, without abandoning the structural theme. From the outside, it may look like routine portfolio management; to those who follow him, each rotation feels like a quiet signal about the next fault line in the cycle.

Perhaps the most intriguing part is how Druckenmiller speaks about his own mistakes – like during the 2000 tech bubble, when he admitted being sucked in too late to a move he already thought exhausted. At a time when the line between finance and politics is blurring, and great fortunes feel compelled to comment on everything – AI, the US budget, inequality – his silhouette as kingmaker raises a question: how far can a single investor, through size, network and public statements, really shift the fate of a currency, a government, an entire sector?

Receive market insights (and more) on the first and third Friday of each month.

If you enjoy this newsletter, please share it

Investments

“The dollar, our currency, your problem”

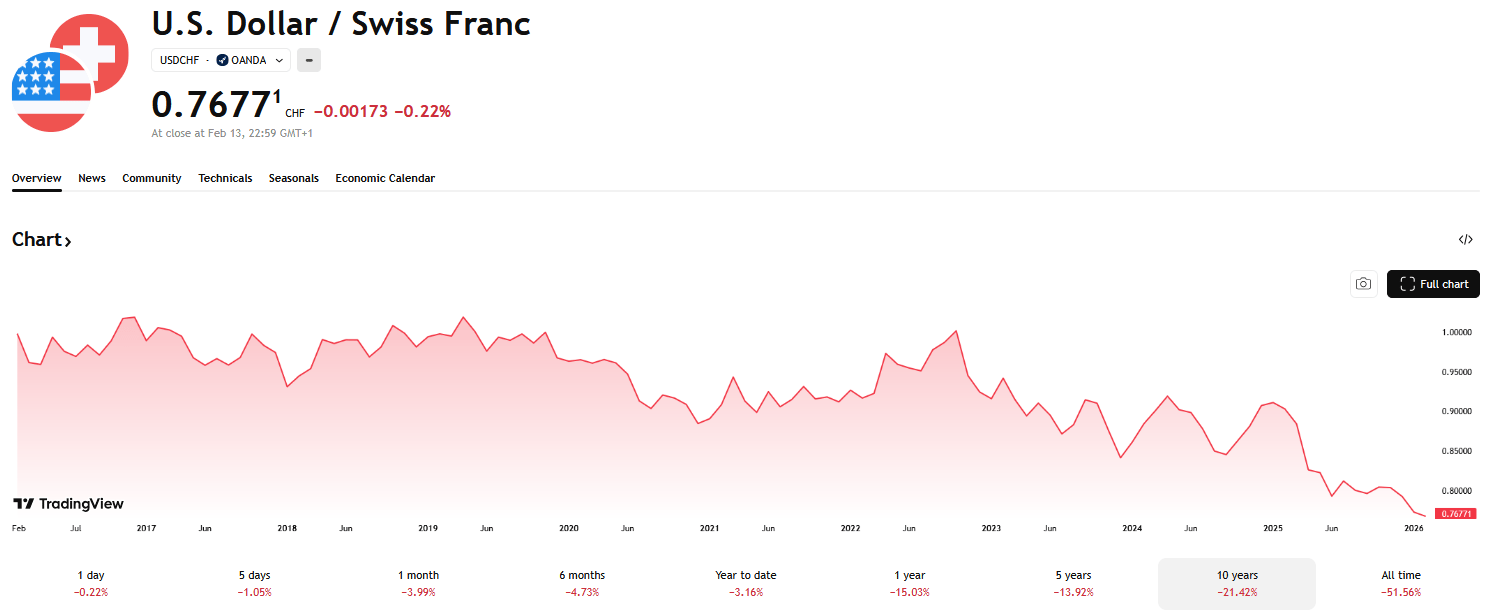

For four or five years now, the Swiss franc has once again behaved as the world sees it: a shield against the spending excesses of politicians of all stripes. Against the dollar, we have moved from roughly 0.95–0.90 Chf for 1 Usd in 2020–2021 to below 0.80 today, with the franc strengthening markedly, especially since 2023. Against the euro, the move has been just as striking: Eur/Chf has slid from around 1.08–1.10 in 2020 to roughly 0.91–0.92 Chf per 1 Eur today, cementing the franc’s role as the region’s safe‑haven currency. For an investor whose reference currency is the Chf, this means that the performance of a portfolio in Usd or Eur depends at least as much on FX as on the markets themselves.

A simple three‑step example

A Swiss investor has Chf 100'000 in cash. He decides to buy Amazon shares in the US because he believes in the company’s model and growth. He converts his francs into dollars at today’s rate – say around 0.80 Chf for 1 Usd – and ends up with about Usd 125'000 invested in Amazon. At this point, he carries two risks: Amazon’s share price and the Usd/Chf exchange rate.

To neutralise the FX risk over one year, he asks his bank or wealth manager to put a hedge in place. Technically, this means selling Usd forward against Chf: he signs a contract today that basically says “in one year, I will sell back my Usd at rate X, already known”. That X is not today’s spot rate, but a forward rate that embeds the interest‑rate differential between the US and Switzerland: because US rates are higher, the market “charges back” part of that extra yield in the form of a one‑year hedging cost.

During the year, Amazon can go up or down, the dollar can rise or fall – it doesn’t really matter: at maturity he will sell his Usd at the agreed rate, whether the market is at 0.75 Chf per dollar or elsewhere. If he has fully hedged his exposure, his performance in Chf will essentially be Amazon’s performance minus the cost of the hedge (linked to the rate differential and technical fees – around 0.05 Chf in our simple example). In other words, he has turned a US equity investment into a “pure” bet on Amazon, as if the stock were quoted in Chf, while paying an invisible annual premium so that FX doesn’t spoil the story.

Put differently

Behind most technical solutions lies a simple idea: you borrow in one currency and lend in another, and you either enjoy or suffer the interest‑rate gap between the two. That, in more sophisticated language, is the carry trade. In plain English: you make money when you are long the higher‑yielding currency and short the lower‑yielding one. A Swiss investor who wants to protect himself against a weaker dollar gives up part of the dollar’s higher carry in order to “buy” FX peace of mind in Chf. Over the long run, several studies show that this peace of mind has a cost: Chf/Usd‑hedged portfolios tend to underperform those that accept some FX volatility, precisely because of that recurring drag (UBS research).

Safe‑haven currencies usually come with low interest rates. One might therefore ask whether high Usd rates are not the mirror image of a gradual loss of interest in the dollar as a safe haven – a currency that no longer quite plays the role it once did.

Financial markets are generally unpredictable. You therefore have to consider different scenarios… The idea that one can truly predict what is going to happen runs counter to the way I look at markets.

B-R & H Finance

Founded in 2004, B-R & H Finance SA is a Swiss entity specialized in wealth management. We offer a full range of personalized and independent investment services and advisory solutions. Regulated by SO-Fit and authorized by FINMA, we are also members of the ASG (Swiss Association of Independent Asset Managers) and work with leading custodian banks.

Affiliate Programs and Sponsored Content: Please note that while we strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information, we are not responsible for the content of external sites referenced in our articles, reports, or any other materials. Some links may direct you to affiliate programs or sponsored content, which will be indicated by an asterisk (*). We do not manage or endorse the privacy practices, content, or policies of these third-party sites. We encourage you to carefully read their privacy policies and terms and conditions before engaging with them.

Disclaimer: This newsletter is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice, a recommendation, an offer, or a solicitation to buy or sell securities or adopt an investment strategy. The information, opinions, and analyses presented here are based on sources believed to be reliable and are expressed in good faith, but no explicit or implicit guarantee is made regarding their accuracy, completeness, or reliability. Stock market investments are subject to market and other risks, and there is no guarantee that investment objectives will be achieved. Past performance is not indicative of future results.